textbender 0.0.7 + Emacs

Simplex-Wide Demo

Now obsolete, this is posted as an example of the simplex-wide approach to recombinant text.

Set Up

This section details set-up of the interface between the Recombinant Desktop and Emacs.

this part deleted

Find a Text

One way to begin is to find a text, and make a copy of it. A population server is a good place to look. It stores its texts in a filebase called the fold, which you can browse. For example:

link and other content deleted

You can browse the fold. If you find the right text, you can copy it. Assume (just for example) you are interested in this one:

link deleted here

To copy this text to your own workstation, use the facilities of your Web browser (e.g. File|Save).

Then load the file into Emacs.

Or, if you prefer to start from a blank page, you can load a copy of blank.xht [link deleted].

Edit

Editing is one way to alter a text. Another is recombination. We begin with editing.

|

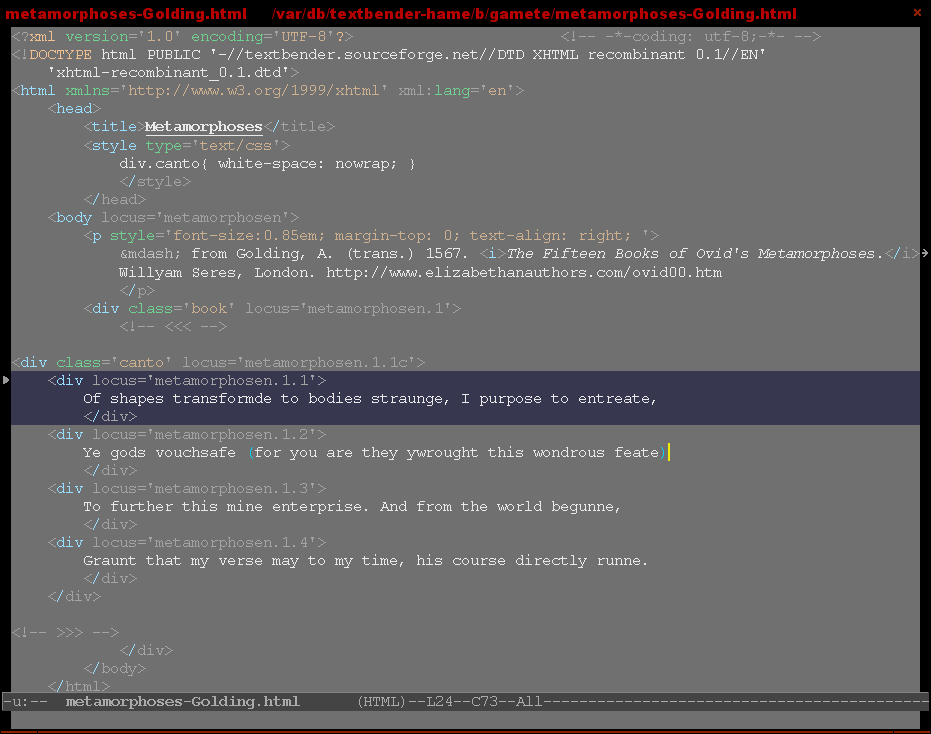

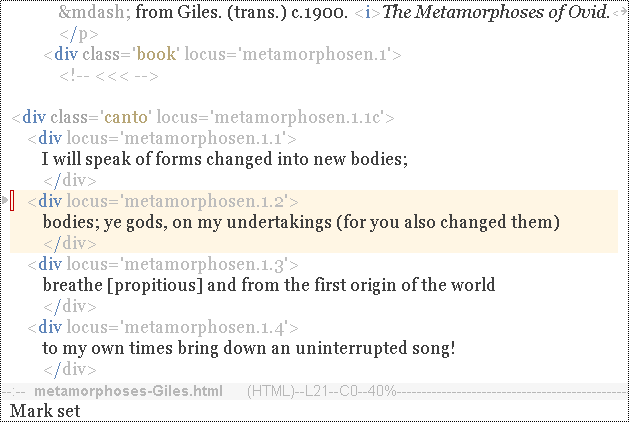

The physical appearance of the encoded text will depend on the capabilities of your terminal or windowing system, and your own customization of ‘font locks’ and faces.

Unless you chose a blank page, you will see elements, some of which have locus attributes. They are genes. Scroll down to the first line in The Metamorphoses for example, and you will see that it is encoded as the gene:

<div locus='metamorphosen.1.1'>

My mind inclines [me] to speak of forms changed into new

</div>Mark a Gene

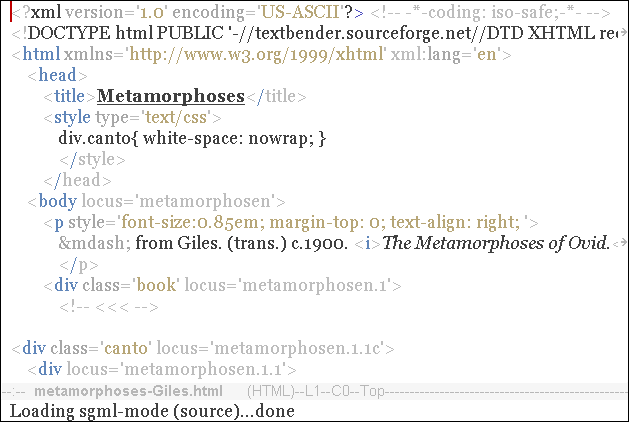

With point on the first line of a gene, the command C-c g (mark-gene)

moves the region to cover all lines of the gene.

In transient-mark-mode, the lines are also highlighted.

|

Create a Variation

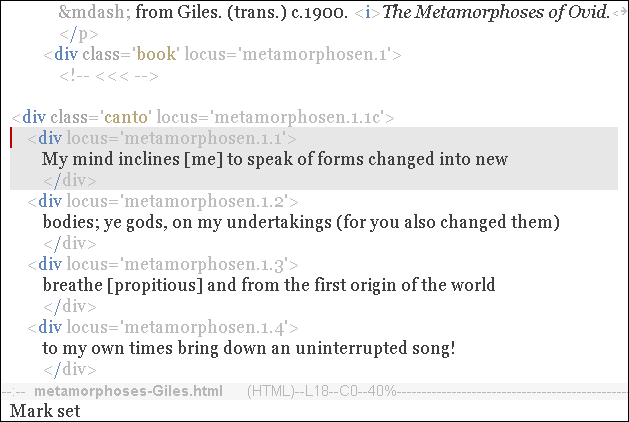

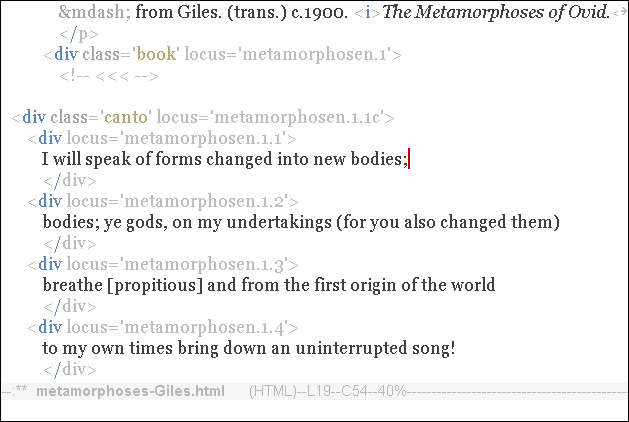

When you alter the text within a gene, you create a new variation of that gene.

|

In this simple example, the new variation is:

<div locus='metamorphosen.1.1'>

I will speak of forms changed into new bodies;

</div>That is all you need at this point, just one new variation.

Or, if you like, you can create an entirely new gene. Follow the same pattern of markup. A couple of pointers:

- For verse use <div> tags, for prose <span>.

-

Leave out the locus attribute

and

textbender.seq.claimprocessing instruction (not shown in screen shots). They are created automatically later, by the claims generator.

Publish

To publish a text, you upload it to a population server. At the moment, the only way to upload a text is via the Web text editor. For the default server (unless you have chosen another) try:

link and other content deleted

That completes publication. Your text and variations are now visible in the gene pool.

Recombine

In the previous sections, you edited a gene and published your altered text. As a result, you contributed a new variation to the gene pool. In this section, you will do the reverse: you will take an existing variation from the pool, and merge it into your own text.

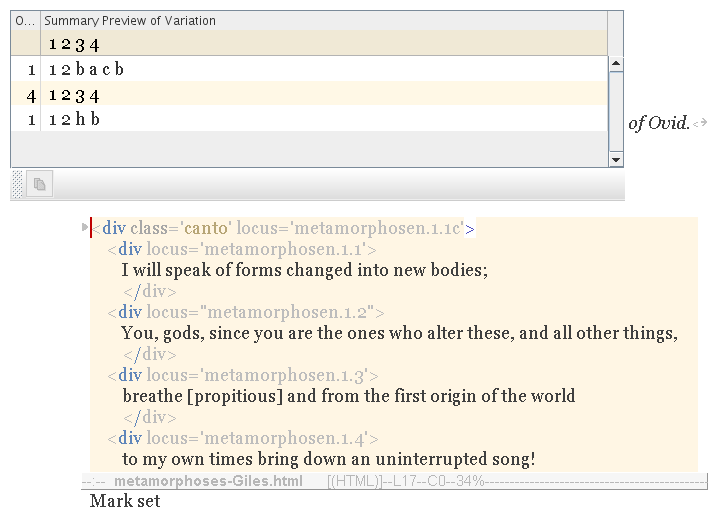

With point on the first line of a gene, use the command C-c t (shift-target-gene).

|

The gene is highlighted with 'target-gene-face' (orangish background), and Emacs launches the Swing toolset. A menu bar appears on your desktop:

|

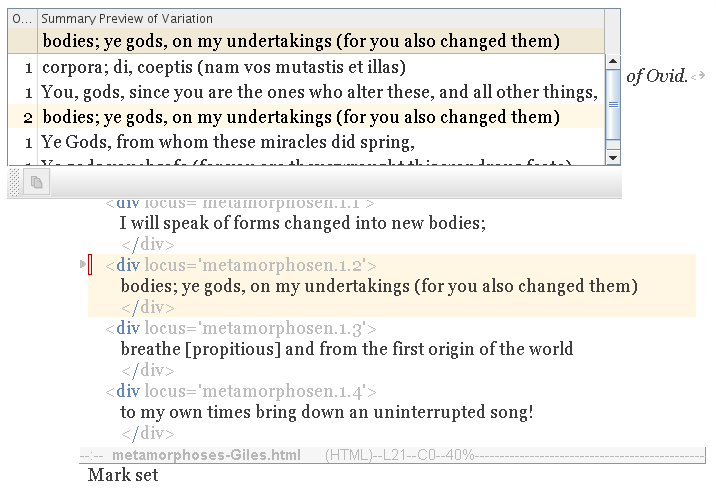

Use its New menu to launch the Allele Table tool.

A table appears, showing variations from the gene pool. It is a window into the population, into the published texts of other writers.

|

Highlighted (top of table) is the reference variation. It is the variation from your own text. It also happens to exist in the wild population (twice). (Which is to be expected, the text having just been published.)

Each variation may occur in any writer's copy of the text (not just your own). So the population may have multiple occurences of it. The Occurences column (far left) counts the number of texts in which the variation occurs. So it measures popularity.

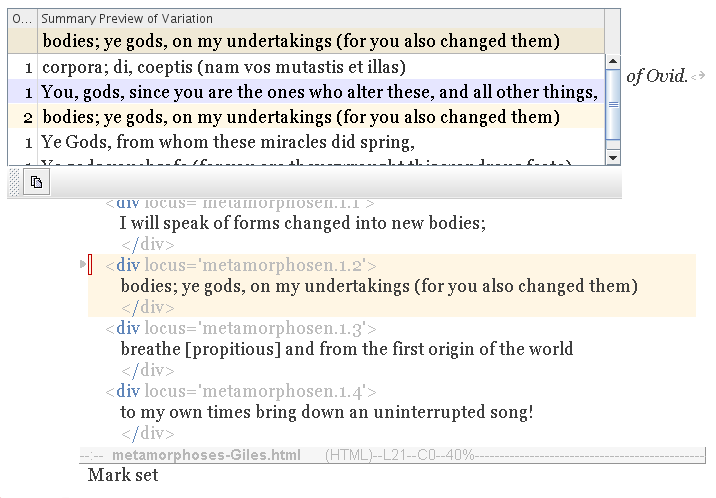

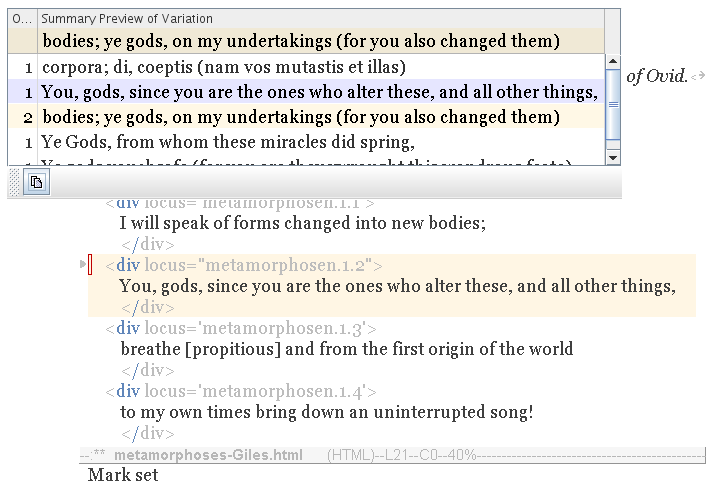

If you select a variation, the Copy button is enabled, as shown here (bottom left of table):

|

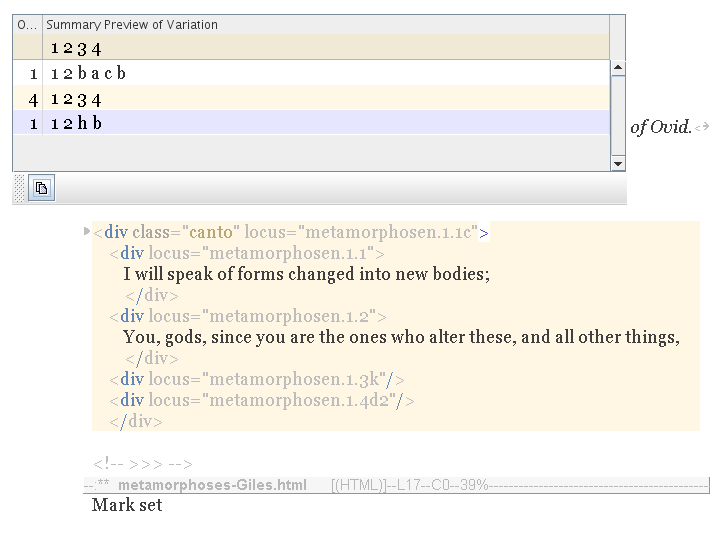

Press the Copy button, and the variation is merged into your text.

|

The new variation is doctored with indentation and other markup to merge neatly into your text, with a minimum of disruption. Your old variation is saved to the kill ring, and point and mark are reset to cover the gene, which remains targetted and highlighted.

Recombine a Parent Gene

Next, we demonstrate how to merge a whole canto, instead of a single line.

With point on the first element of a canto,

use C-c t (shift-target-gene) to target it.

The canto is a structural parent gene; the lines nested within it are leaf genes. Whereas a line/leaf gene encodes variations of characters; the canto/parent gene encodes variations of line arrangement. These variations are summarized in the table (below).

|

As you can see, most writers prefer the same arrangement of lines (1 2 3 4) as you. And everyone has the same two lines (1 2) at the beginning of the stanza. Or rather, variations of the same two lines; because, although all writers have line 2, for example, that line has variations (as we saw previously).

But those lines (b a c b, and h b) in the other arrangements, they are considered to be essentially different from 3 and 4. And none of them exists in your own text.

Unfortunately, none of this information is especially helpful in making a selection. In fact, recombinant text is probably limited to simple recombination, e.g. of lines and phrases. Other techniques and tools are needed, really, to recombine higher orders of variation, e.g. of cantos, paragraphs, and whole chapters. [Later implementation of compound gene transfers necessitated a redesign of the communication architecture, superceding the simplex-wide approach, described here.]

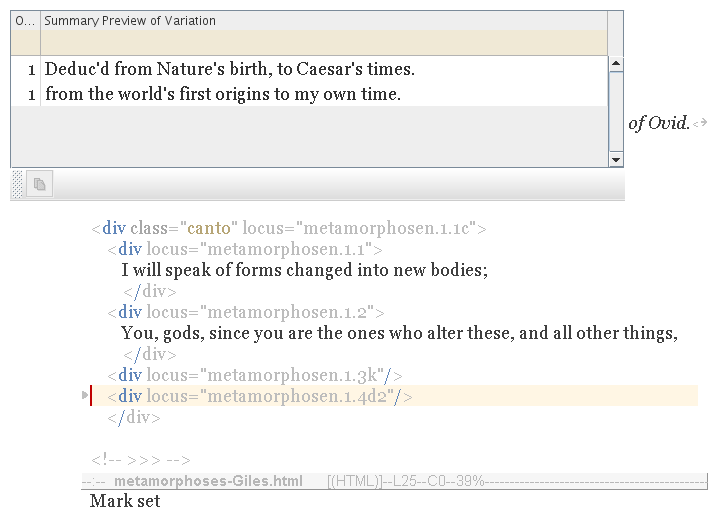

Nevertheless, if you were to decide somehow in favour of the last canto variation (above) then you could select it, and press the Copy button, to merge it into your text.

|

Notice that the variations inside the lines are unaffected, as far as possible. You still have what you chose earlier for lines 1 and 2.

The third and fourth lines remain a mystery. They are empty. But they are genes, so we can search for variations, and fill them in. In future, the tools will automatically do this, using common choices or best guesses; but for now, you would have to do it manually.

Simply target one of the empty genes (as shown below); then select and copy — all as described previously.

|

That completes the walk-through. As you can see, the text was not greatly improved. Hopefully we can try again later, when the tools are better developed.